By Alessandro Federici*

The stereotype is that modern slavery is only a problem in the most distant countries. The reality, instead, is that you don’t have to go far to find it. From the deep south of Spain to the northern latitudes, the European Union is in fact afflicted by the scourge of labour exploitation, which for years has involved several member states. It is no coincidence, then, that even in the highly civilised Netherlands, home of the welfare state, there are around 33,000 workers who are victims of exploitation. About 2000 cases of exploitation every year.

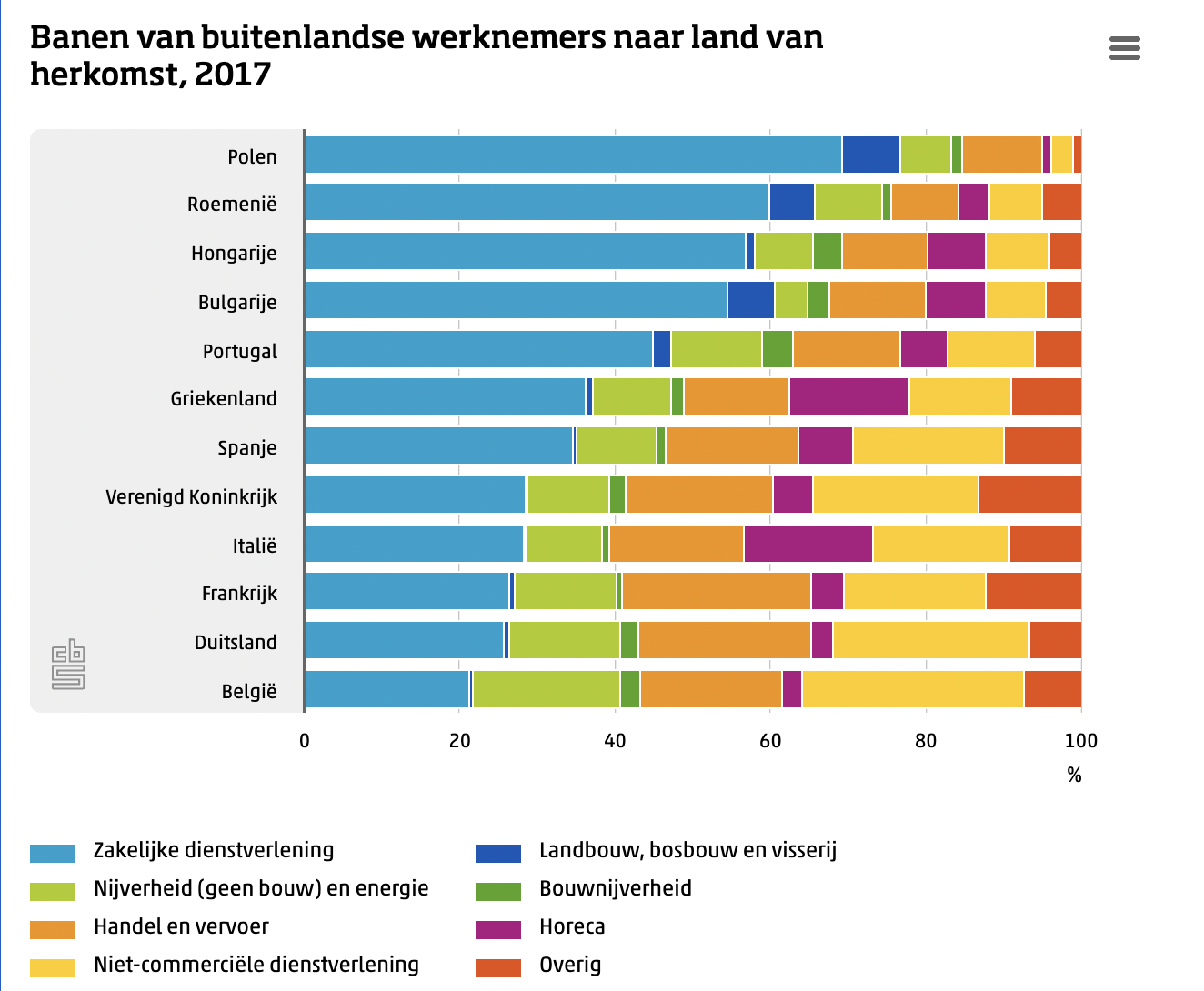

According to a study financed by the Open Society Foundation, almost 500,000 migrants have arrived in the Netherlands. They come mainly from Eastern and Central Europe, and constitute the largest workforce in the most significant sectors of the Dutch economy: agriculture, and the meat industry. Driven by the hope of improving their living conditions and social position in a country that allows upward mobility, they very often come up against a completely different reality made up of exploitation and inhuman living conditions, where most of the jobs they do are characterised by what Maurizio Ambrosini, expert sociologist on immigration, calls the five “p’s”: precarious, dangerous, heavy, poorly paid and socially penalised.

Barka, an organisation that supports and assists people from Central and Eastern Europe who find themselves in a situation of great hardship, explains that most people are hired through temporary agencies in the migrants’ countries of origin. The latter may be local offices of Dutch agencies, located in that particular territory, or agencies in the countries of origin that cooperate with Dutch recruitment companies. In recent years, the number of such agencies has increased, and according to a government report, many abuse the fragile position of migrants by imposing conditions on them, which in fact negate any kind of protection.

The Dutch system, both in terms of legislation and controls, seems to be experiencing a harsh crisis, and it is the migrants who pay the price. The collective labour agreement for temporary workers recognises three types of contracts, each of them situated in three different phases, explains Anna Ensing of Fairwork, an association that supports victims of labour exploitation in the Netherlands. In phase A we find the contract with a temporary work clause. The latter can end immediately and at any time, and workers are only paid for the hours they work (zero-hour contract). This stage implies a constant risk of dismissal and high income insecurity. In stage B, a contract for a fixed period takes over, usually for a maximum of three years. Within this stage workers find more protection and security, receiving, unlike in stage A, a fixed monthly income. In phase C, an open-ended employment contract is concluded. Again, Anna Ensing of Fairwork, makes it clear that this structuring is problematic for workers, as employers and temporary agencies prevent workers from progressing beyond the first phase of the contract. As the Open Society European Policy Institute study reports, this is beneficial for both agencies and employers. The former, by signing more and more contracts and thus recruiting more and more workers, receive higher fees. The latter, on the other hand, save on wages and fringe benefits. It is important to point out, according to Piotr Jackiewicz of Pauluskerk Rotterdam, that 10% of migrant workers arriving in the Netherlands are not aware of their rights, because the contracts are not written in their language of origin, nor in English.

In order to obtain, but above all to keep their jobs, the workers have to work under very poor conditions. Stichting Loods, an association that takes care of people in vulnerable situations, and takes in people subject to labour exploitation, lists some of them. They talk about exhausting work shifts; from 12 to 14 hours, low wages, well below the guaranteed minimum wage in the Netherlands, and abuse. Another issue is that of housing. According to contractual conditions, employers or agencies provide workers with accommodation.

Very often these lodgings are real shanty towns, where migrants live in appalling and inhuman conditions. In addition, rents are very high: 150-200 euros per week. Another critical point is that once a migrant has lost their job, they are obliged to leave the accommodation within 24 hours. In the worst case, effect immediate. This inevitably means that many of them end up living on the streets, having nowhere else to go. “Efforts are being made to remedy this situation with new contractual arrangements, which would allow people to leave their homes within two weeks of losing their jobs, but it is still not enough”; says Anna Ensing of Fairwork.

One could always say enough, but it is not that simple. Exploited workers do not always leave. Transport, health insurance and housing are often linked to the employment contract. All these conditions lead to a strong dependency on their employers and thus to a refusal to report cases of exploitation for fear of losing even the little they have. Even when victims seek justice, it is rare to obtain it. In fact, according to Investico, a Dutch platform for investigative journalism, reports that only one in fifty complaints leads to a conviction. The investigation shows that the line between exploitation and employer misconduct is often too vague for the authorities to intervene. The social context of the migrant workers’ countries of origin also plays an important role. Most of them come from the most fragile and poor economies in the EU. Once they arrive in the destination countries, despite the fact that reality does not meet their expectations, due to the various violations they suffer, they feel richer, and paradoxically, more satisfied with their ‘new’ living conditions. This is alarming because, partly due to a lack of social and cultural tools, they are not aware of the exploitation and countless violations to which they are subjected every day.

As reported by various organisations and activists working on this issue, to date, the Dutch government, apart from several promises and the establishment of a task force to protect migrant workers during the Covid-19 outbreak, has done nothing concrete to remedy this problem. Moreover, controls are practically non-existent. Only 1% of companies are checked annually by the labour inspectorate.

*: This article is part of an educational-journalistic collaboration between the Atlas of Wars and Conflicts in the World and the Italian Association Papa Giovanni XXIII. The authors are young people between 18 and 28 years old who are abroad on humanitarian or civil service missions.