Between 2014 and 2018, records have tracked more than 8400 significant cyberattacks, publicly recognized as sponsored by state actors or government-affiliated organizations. Of these, 323 were major operations conducted against government agencies, private defense companies, information and communications technology (ICT) companies, or attacks to critical civil infrastructure or economic assets that have caused losses of more than a million dollars.

With these numbers in hand, some analysts have come to hypothesize that the Third World War has already begun and is being fought online. Moreover, the emergency caused by the Covid-19 pandemic has shown that the Internet is an equally critical part of our global infrastructure, and therefore just as vulnerable: just like other civilian systems, its correct functioning is essential to guarantee effectiveness of many vital services for society (power and nuclear power plants, oil pipelines, dams, ports, railways, banking, administrative and health institutions). There are strong concerns from some of the most digitized countries about the increase in cyber attacks against hospitals and vaccine research centers, and calls for a safer cyberspace, especially now, are equally intense.

If humanity has managed to build a future – represented by its infrastructures – it seems, however, that at present it is not able to protect it from threats of a digital nature that derive from exploitation by different actors (state, non-state and artificial intelligences) of the vulnerabilities of information and communication technologies (ICT) and the respective (in)capacity of the target-victims to minimize their consequences. The effects of these insecurities can be assessed on a double front, technical and content-related, in terms of impact on the availability, confidentiality, and integrity of system data, on the one hand, and of sensitive infrastructures on the other.

Incidents resulting from acts of sabotage, potentially able to cause both causalties and lasting and significant damage to industrial facilities and critical infrastructure, are an example of such vulnerabilities; another example is the use of ICT to interfere in a State’s internal affairs, to influence political decisions or to destabilize the national economy. To this date, no events with dramatic humanitarian consequences have occurred, but even if we are not yet able to measure the full military potential of the virtual space, it is now clear that targeted operations against sensitive infrastructure networks are technically possible, generalized (hence no longer targeted), with large-scale potential damage.

This has led to growing tensions and an increased decline in trust between states (especially between digital powers) which has made the current debate on the regulation of cyberspace increasingly complex, precisely because the conversation is entwined with strong political features, especially with regards to the protection of international peace and security.

Defined as the “fifth dimension” of conflict, cyberspace has therefore become, on a par with land, water, air and space, a new theater of war, creating a particular challenge for the stability of international relations since the international system traditionally refers to sovereignty – a concept that is essentially expressed in a political-territorial dimension. Cyberspace, on the other hand, is a “non-place”, an entity without political or natural boundaries in which anonymity prevails, with consequent problems of attribution of conducts and behaviors relevant to the attribution of legal responsibility.

In this dossier we will introduce the theme of the stability of cyberspace, of cybernetic armed conflicts and cyberwarfare, which for some years have been occupying the first points of the agenda of the International Community due to the strong political-strategic connotations and technical-legal implications of a field – the numerical one – the defensive and offensive militarization of which represents a unicum in the history of arms control for its multilevel architecture and for the numerous actors involved in it (multistakeholderism).

Cyberspace is accessible to governments, international organizations, non-governmental organizations, private companies and individuals, and with all these subjects on the “public square” the simple use of a falsified identity (Ip spoofing) or a network formed from PCs connected to the Internet and infected with malware could camouflage and hide the origin of an operation,thus making extremely difficult to identify and attribute responsibilities of cyber activities.

We are therefore faced with new risks and new vulnerabilities that make the hostile use of cyber space a very topical issue. And although most of the cyber attacks experienced to date do not have to do with an armed conflict as defined by international humanitarian law, the development of military cyber capabilities and the possibility of their use in the context of an armed, cyber conflict tout court or mixed (kinetic and cybernetic), generate a growing feeling of insecurity between states and the entire international community.

The need to identify a global discipline applicable to the digital dimension therefore arises from the primary need to make state actions in this space ever more predictable. Furthermore, it is increasingly essential to establish international cooperation and coordination mechanisms at different levels and between different actors, with preventive and response functions with respect to potential incidents or attacks on state cyber security and sensitive infrastructures. Also, in order to avoid dramatic implications due to Covid-19 for international peace and stability, the most computerized countries are denouncing in all international fora how crucial multilateral cooperation is for collective health, prosperity and security.

A historic step forward in this sense came last March from Estonia, remotely holding the Presidency of a United Nations Security Council meeting for the first time. Supported by the United States and the United Kingdom, the Estonian Presidency formally raised, for the first time in the history of the Council, the issue of international stability in cyber space and that of new digital threats, confirming the attribution to the Russian intelligence service (GRU) of the cyber attacks against Georgia of 28 October 2019. Estonia holds numerous records in the cyber sector, being one of the most digitized countries in the world and one of the first to have suffered, in 2007, the blocking of the IT systems of banking institutions and of the whole public administration by a series of large-scale cyber attacks. The scale of such attacks, is believed, could have triggered art. 5 of the NATO treaty which provides for the collective defense of the attacked state.

In 2020, cyber attacks have been more frequent and we will account for them in this dossier, trying to understand the consequences on international balances. We will follow the evolution of the attempts to regulate cyberspace at an international and regional level, especially in light of the dramatic impact that the global health crisis adds to global peace and security.

The features of the cybernetic "war theatre"

The nature of cyber warfare is informed by the definition of cyberspace; moreover, its relevance or (ir) relevance (only the future will determine this) for international humanitarian law, because only in the light of the analysis of the characteristics of this dimension can be understood how difficult it is to interpret and apply the existing ius in bello which, for some States (USA, United Kingdom, Estonia, Israel), should be – and remain – the only regulatory source of cyber operations.

An oxymoronic term like cyberspace indicates the only dimension entirely built by man that is not an actual space as such. This is a “non-place” created, maintained, owned and made operational collectively by public and private entities (stakeholders) throughout the hemisphere and which undergoes constant, daily changes in response to technological innovation.

All of these features have numerous advantages in potentially conducting offensive cyber operations and make it a prime location for warfare.

- Let us consider that its creation and management is entrusted simultaneously to military structures and private companies, considerably increasing the number of sensitive targets.

- The continuous technological developments, as well as the connectivity and interdependence between this dimension and the equipment operating in the other domains while on one hand improving human activities, on the other increase their vulnerability.

- Cyberspace is not subject to political or natural boundaries: the information or contents loaded into it are distributed almost instantaneously from a point of origin to any other connected destination in the globe, through an electromagnetic spectrum, allowing lightning attacks to be made even at long distances, without the need for direct physical confrontation.

- The programs / software needed to operate in cyberspace reduce the margin of human error since it is not subject to variables from other domains (such as atmospheric agents) and therefore involves a high capacity for human control.

- Cyberattacks are less expensive in terms of time, means and human resources: the mass production of “weapons” in cyberspace is considerably faster and cheaper than conventional ones.

- In principle, compared to kinetic weapons, in virtual space it is possible to launch attacks that are generally less lethal (but this must be proved) both for fighting troops and for the civilian population, but economically more devastating and dangerously destabilizing.

- Cyberspace allows its users to operate in full anonymity and hide behind the activities of other subjects (hackers, criminal or terrorist organizations, foreign agencies, nations), favoring minimal exposure to the risk of accusations and counterattacks.

- Finally, it allows viruses to replicate exponentially and this circumstance gives the attacker the advantage of being able to create additional effects, capable of spreading virally, even with a limited initial effort.

Cyberspace is understood as an unprecedented “revolution” – a space revolution – which opens to being examined from a plurality of perspectives, including diplomatic and legal perspectives, which are questioning its regulation. Starting from its most peculiar characteristics, cyberspace solicits international law under numerous profiles (e.g. big data, privacy and human rights, cyber security and cyber war) and is forcing the international community to question the need to interpret and / or review some classic legal categories or alternatively to create new ones.

Covid-19 and cyberattacks

The coronavirus emergency has prompted the reorganization of work by expanding the methods of remote smart working, in order to avoid gatherings and limiting the use of public transport. But at the same time, the threat of cyber attacks by international terrorist groups has grown.

Since March 2020, there has been an unprecedented global increase in malicious cyber activity. Phishing attacks aimed at stealing money or information from home workers have more than doubled since last year and in some countries have increased sixfold; Numerous cyber attacks on critical infrastructure including airports, power grids have also been detected, and neither ports or water and sewage facilities have been exempt. Some hospitals engaged in treating COVID-19 patients have also been targeted, and the World Health Organization (WHO) has reported a fivefold increase in attacks on its networks.

It was July 16 2020 when the United Kingdom publicly denounced suffering from cyber attacks by non-state actors affiliated to the Russian government, called Apt29. Such attacks are targeting organizations involved in the development of the coronavirus vaccine with the intent to steal valuable intellectual property.

WHO DOES WHAT: The Cyberspace

An internationally accepted definition of cyberspace has not yet been identified, and this is the first aspect that makes the process of regulating cyber operations very complex. The term cyberspace has different meanings depending on the State or the International Organization making use of it, and only recently States have felt the pressing necessity to undertake a process aimed at standardizing the definitions, with the help of glossaries shared in international or regional platforms (UN , OSCE, NATO, SCO).

Most of the utilized definitions are extrapolated from the National Strategies relating to cyber security; others refer to the few international regulatory references, such as the two Tallinn Handbooks (2013-2017) on international law applicable to cyberwar and cyber operations which, however, are merely non-binding provisions. In the Manuals, cyberspace is defined by the group of international experts who drafted them under the auspices of NATO, as “the environment formed by physical components, characterized by the use of computers and an electromagnetic spectrum in order to store, modify and exchange data via computer networks”.

FOCUS 1: The Risk of Cyberattacks

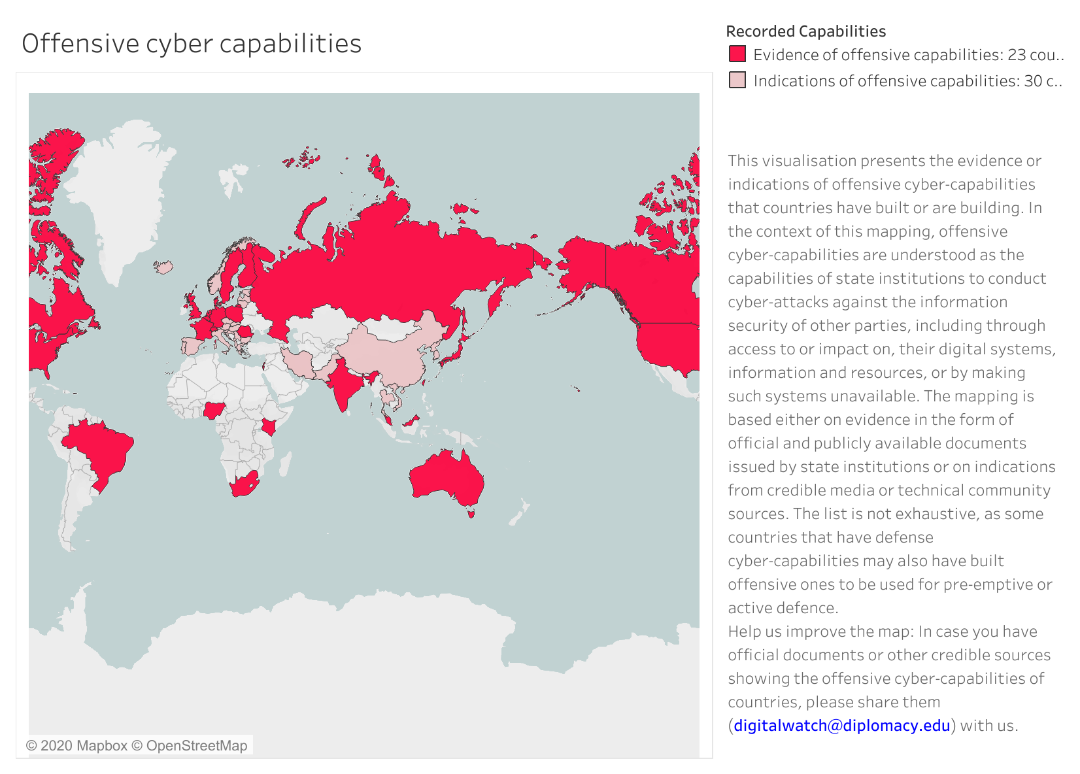

For the past decade, the growing awareness of states and major companies in the digital world of how real and significant are the risks that cyber activities pose to international peace, security and stability has been clashing with increasing economic investments by governments in scientific programs aimed at developing the defensive and offensive digital capabilities of cyberspace, the militarization of which is de facto inexorable and already completed. Although the need to de-escalate the tensions that could lead to a cyber conflict is invoked daily not only by the most digitized states (USA, Israel, China, Russia), but also by those with less technological power and by the private sector, we are witnessing an inexorable change in the paradigms of national defense strategies from which it is not difficult to infer the willingness of States to no longer ignore the protection of sensitive data in the face of an acceleration of the so-called “digital uncertainties”. The US’ National Defense Strategy is a clear example of this: it lists cyber risk among the types of threats that can receive a nuclear or weapons of mass destruction response.

From such premises, there is no doubt that the uses and abuses of this complex, unlimited virtual space can come to violate the vital interests of states in the physical world, undermining national security, democracy and economic development. Cyberspace, understood in a broad sense, is therefore a significant phenomenon for diplomacy (recently reference is increasingly made to cyberdiplomacy) and consequently for international law

FOCUS 2: Cyber Operations: some examples

The cyberspace extends far beyond the domain of internal affairs of each state: it is therefore imperative to clarify the boundaries between the autonomy and boundaries that apply to actors operating in cyberspace, taking into account the fact that their online activities can trigger off conflicts offline too.

Some striking examples may be useful to understand how rapidly hostile attacks in cyber space are becoming “legitimate means”, increasingly used by States and non-state actors in the fifth dimension. While we do list the most eclatant ones, it is important to note that only some of them can be included in the definition – albeit still in an embryonic state – of cyberwarfare operations.

- 2003 – The United States accuse China of being in charge of Operation Titan Rain, which targets several American electronic devices.

- 2006 – Stuxnet case: a computer virus, created and purposely spread by the US government, in collaboration with the Israeli government, as a penetration digital bomb, attacking the Iranian nuclear program (in the Iranian nuclear power plant of Natanz) in order to sabotage the plant’s centrifugel through the execution of specific commands to be sent to the industrial control hardware responsible for the rotation speed of the turbines in order to damage it.

- 2007 – Estonia suffers a series of generalized and large-scale cyber attacks that block the critical IT systems of public administration and banking entities for a few days.

- 2010 – Wikileaks publishes thousands of US State Department classified documents.

- 2014 – The world witnesses one of the biggest attacks in history launched by North Korea on Sony Pictures with files stolen, copied and deleted from hardware.

- 2015 – Following the Turkish downing of the Russian jet in Syrian airspace, Turkey suffers for several days from an escalation of systematic and generalized attacks that bring the country to its knees.

- 2017 – WannaCry and Petya ransomware, started in Russia, spread on a global scale, attacking the devices of various sensitive infrastructures in numerous countries. One of the radioactive monitoring systems at the Chernobyl power plant is taken out of use and numerous French companies suffer a computer system crash. Denmark, Great Britain and the United States are also among the victims, but it is in Ukraine that the greatest inconveniences are caused: the malware has allowed attackers to alter the functioning of some substations of the electricity grid. The result is a blackout which affects about 80,000 users and causes the closure of the Kiev airport. It is the first known case in the world of blackouts caused maliciously – that is, not due to failure or human error – by “cyber” means.

- 2019 – Georgia suffers disruptive large-scale cyberattacks against a number of national web hosts that disfigure websites, including sites belonging to the government, courts, non-governmental organizations, businesses and the media even with service disruption from various national broadcasters. The public attribution of the illegal conduct to Russian cyber intelligence (GRU) is formally declared for the first time in the history of the United Nations Security Council in March 2020, by the representative of the United Kingdom. As part of a long and systematic campaign against Georgia, the intent of the attack would have been to undermine Georgia’s sovereignty and disrupt the lives of the Georgian people.

- 2020 – In an attack last April, promptly neutralized by Israel’s National Cyber Directorate and resulted in no consequence, hackers linked to the Iranian regime attempted to sabotage the water systems of two towns in the Jewish state. Tel Aviv’s reaction targeted the Iranian port of Bandar Abbas, causing the paralysis of most commercial activities of this strategic infrastructure for at least three days.