By Alessandro de Pascale

The Native American and Alaskan tribes have reached an economic agreement with the well-known pharmaceutical company Johnson & Johnson and the three largest distributors of prescription opioids in the United States (McKesson, AmerisourceBergen and Cardinal Health). The agreement has been described by many as ‘a historic achievement’. But it now needs to be implemented, in order for the tribes to receive the $590 million put up for them in the maxi-litigation over the so-called opioid addiction epidemic (involving psychoactive drugs with morphine-like effects).

In detail, the agreement announced on 1 February provides for 150 million over two years for the natives to be paid by Johnson & Johnson, and the remaining 440 million over seven years that will have to be provided by the three distributors. The funds will be used for addiction treatments: Services that the native tribes, being sovereign states under US law, manage independently.

Profit over public health

“Johnson & Johnson, like all the other manufacturers” – denounces to the Atlas Lloyd B. Miller, a lawyer representing in this litigation about 30 per cent of all Indian tribal communities in America – “has misrepresented its opioids to the medical community and to the public as non-addictive drugs, and recommended them for the treatment of chronic and minor pain. The three drug distributors in question should have reported the excessive demand for prescription opioids presented by pharmacies, thus stopping the sale of that avalanche of pills. They did not, because there was so much profit to be made in continuing to support the addiction”.

In short, claims Miller, these industry giants ‘did not respect procedures’. This has led to an explosion of court cases in the United States, with several economic settlements already signed. In 2017, many of the cases were then partially brought together in a maxi-court action with some 3,000 plaintiffs (most of them government bodies), which has been pending for years in the federal court of Cleveland (Ohio). This agreement is only a branch of the largest lawsuit – the branch regarding almost the entirety of the Cherokee native population.

As early as last September, those distributors agreed to pay more than $75 million to settle the litigation, in which they were accused of fuelling an opioid epidemic among Oklahoma’s Cherokee population of more than 390,000. “The tribes’ claims against several other defendants remain pending, including those against major pharmacy chains (CVS Health, Walgreens Boots Alliance and Walmart, ed.), manufacturers such as Teva, Allergan, Endo and, in a separate case, consulting firm McKinsey,” Miller recalls. In their case, there are two alternatives, the lawyer summarises: ‘Either this will go to trial or these will also be resolved through similar economic settlements’.

The historical settlement: an admission of guilt?

Returning to the agreement reached with the natives on 1 February, the signatory companies reject the accusations. For example, Johnson & Johnson, in a statement released to the media, made it clear that the decision to pay ‘does not constitute an admission of liability or wrongdoing and the company will continue to defend itself against any further litigation’. This is a well-established practice in the United States, given the formulas used in agreements that allow one or more parties not to take responsibility for the accusations.

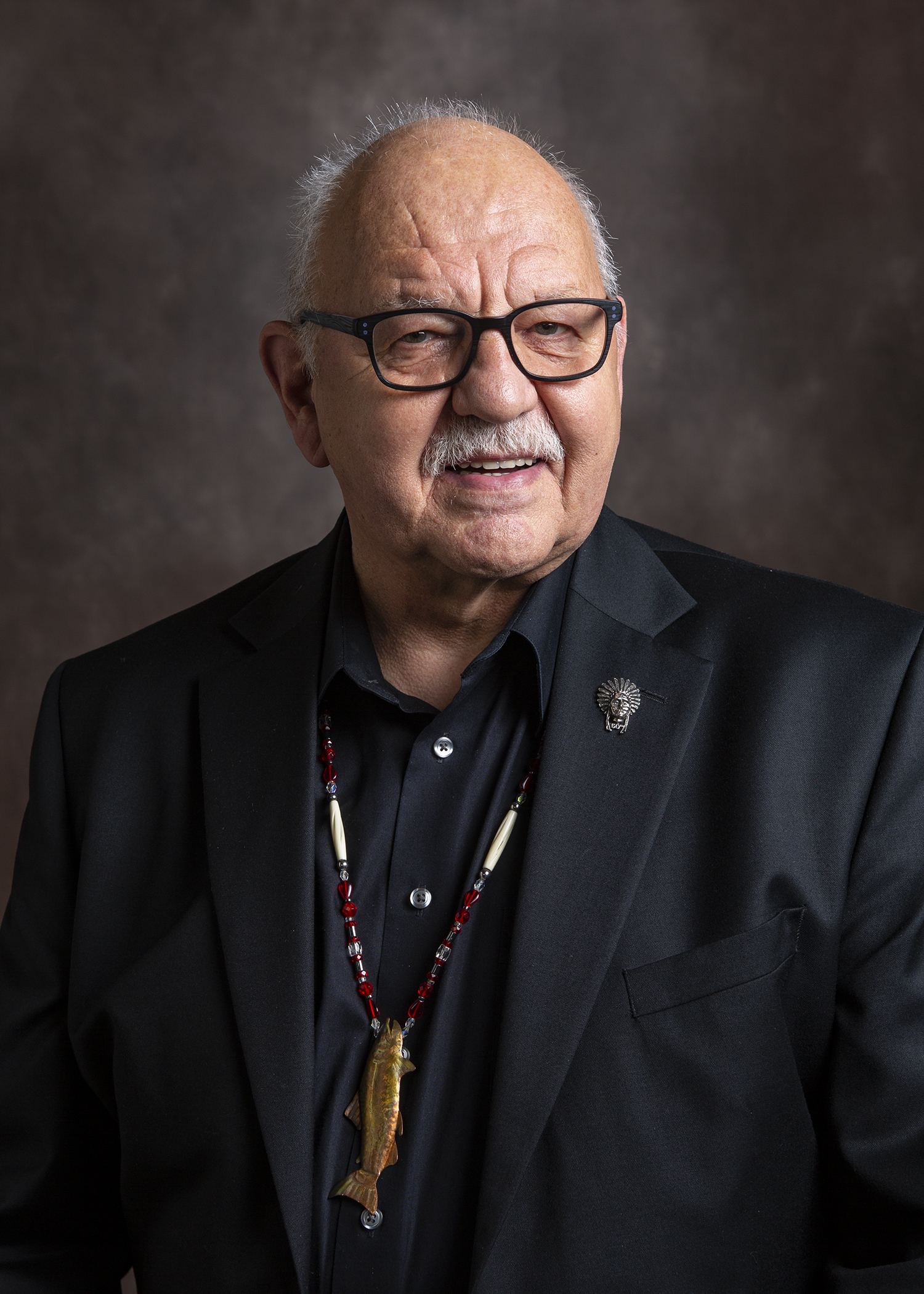

However, says Miller, ‘the payment of USD 150 million to the tribes and USD 5 billion to the United States speaks for itself’. Having reached an agreement in principle between the parties, the game now moves on to the fine-tuning of the criteria. “The tribunal has appointed three very qualified people to work with the tribal leadership to determine the methodology to be adopted,” says W. Ron Allen (left) to the Atlas. He is chairman of the Jamestown S’Klallam (Washington State area) and tribal representative in several US government departments. ‘The allocation of the reparations’ Allen continues, ‘will undoubtedly take into account many factors, such as the number of citizens, the land area of each native community, etc’.

Native tribes: sovereign within the US

Even most important is the fact that this agreement, for the first time, is universal. In other words, all 573 tribes recognised by the US government (all of which count from a few hundred to several thousand members) can access the funds made available, regardless of whether or not they are part of the judicial process. To do so, however, they will have to sign the agreement individually.

‘Within the borders of the United States, native tribes are sovereign governments with their own laws and customs,’ reminds the Atlas lawyer Geoffrey D. Strommer (right), who is representing a dozen other tribes in the dispute, in addition to the Jamestown S’Klallam. “This status,” the lawyer points out, “derives from the fact that the tribal nations existed before the arrival of the Europeans and, when the United States were formed, they did not consent to incorporation into the US, nor did they waive any sovereign rights. All recognised tribes consequently maintain government-to-government relationships with the United States, which in turn recognises their sovereignty,” Strommer explains.

The Supreme Court has consistently upheld this status, recognising that Indian tribes are ‘separate and pre-existing sovereign governments with respect to the Constitution (…) distinct and independent political communities, which retain their original natural rights to local self-government’. It is therefore incumbent upon them, Mr Strommer adds, to ‘protect and promote the health, welfare and future prosperity of their citizens’. But above all, to decide in this case whether or not to sign the agreement’.

The overdose epidemic….

Opioid abuse has long affected the entire United States. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), between 1999 and 2019, these drugs have caused at least half a million overdose deaths in the US, exceeding even heroin deaths in some years. The problem is far from over. For the CoC, only fentanyl, a drug approved for the treatment of pain, killed more than 64,000 people in a single year (from April 2020 to April 2021). On 15 December, US President Joe Biden spoke of a ‘national emergency’. A special Commission to Combat the Trafficking of Synthetic Opioids has been working since May 2020 to develop a ‘strategic approach’ to combating the phenomenon. It is composed of representatives from seven government departments and agencies, four sitting members of both the Senate and the House, as well as subject-matter experts from the private sector, supported by the Homeland Security Operational Analysis Center (HSOAC), a research and development centre funded by the federal government and managed by the Rand Corporation. Their latest report was submitted to Congress on 7 February and contains some worrying numbers: $1 trillion in 12 months is the cost of overdose deaths in the United States (three years earlier it was 700 million) and 100,000 victims in 2021 alone, double the numbers of a year earlier, in what they describe as a ‘shocking overdose epidemic’.

…Affecting the fragile Native population

According to various studies, presented in the tribes’ court documentation, American Indians and Alaska Natives have “suffered some of the worst consequences than any other population in the United States,” including the highest per capita casualty rate. “The impact of the opioid crisis on American Indians and Alaska Natives is immense,” stated Navy Rear Admiral Michael E. Toedt, medical director of the Indian Health Service (IHS) established at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), during a 2018 hearing before the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs. “The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),” Toedt continued, “reported that Native people had the highest rates of death from psychoactive substance overdose and the largest percentage increase in the number of deaths from 1999 to 2015 compared to any other racial and ethnic group in 2015. During that time, deaths increased by more than 500% among American Indians and Alaskans,” the Navy Rear Admiral reported. In addition, ‘due to misclassification on death certificates, the actual number of deaths could be 35% higher’.

The problem of drug addiction among natives is actually not at all new. Michael Kaliszewski is a famous scientist with 15 years’ experience as a researcher. For the American Addiction Center, a public organisation based in Tennessee that treats addiction in residential and outpatient facilities, he summarised why abuse rates among Native Americans are generally much higher than those of the general population in the United States.

Let’s start with the data: according to the 2018 US Census, there are 6.8 million Native Americans and Alaskans. Of these, the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), reports that 10% have a substance use disorder; 4% suffer from a substance use disorder due to illicit drug use; 7.1% have a substance use disorder due to alcohol abuse; nearly 25% report drinking excessively in the past month; and are more likely to report drug abuse in the past 30 days (17.4%) or year (28.5%) than any other ethnic group. Substance abuse and addiction are also among the top concerns of Native American youth. Again, the results of that 2018 national survey show that, among them, nearly one in five young adults (aged 18-25) has a problematic substance use disorder, including 11% due to illicit drug use and 10% due to alcohol.

In addition, about 4 in 10 Native American adolescents (aged 12 to 17 years) have a record in the US for one-off illicit drug use. The same is true for tobacco, with Native American adolescents having the highest lifetime rates in the use of tobacco, marijuana, and non-medical use of analgesics and psychotropic drugs, as reported in the 2014 national survey presented by Kaliszewski. Risk factors identified by the researchers include ‘historical trauma, violence (including high levels of gang, domestic and sexual violence), poverty, high levels of unemployment, discrimination, racism, lack of health insurance, and low levels of educational attainment’.

Mr Miller is well aware that ‘such an agreement is inherently unsatisfactory’. The damage done to tribal communities, he says, is ‘unfathomable’. Not least because ‘many natives will need care and services for the rest of their lives. That said, the alternative would have meant years of litigation and appeals with unpredictable final results. Whereas to provide an immediate response, we need the money now’. And for the first time, unlike in the 1990s with the tobacco companies, Native Americans and Alaskans have been granted special and specific compensation.

Cover image: Sean Foster, Gatlinburg, TN, USA