Reducing violence in all its forms is a fundamental prerequisite for human security and one of the goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Today, some 1.2 billion people live in conflict-affected areas, and almost half of them (560 million individuals) are in countries not usually considered as fragile. Still, violence and fear of violence drive people to leave their homes and seek refuge elsewhere. The number of forcibly displaced people is growing, peaking at 82.4 million in 2020. These are some of the figures provided by ‘New threats to human security in the Anthropocene Demanding greater solidarity’, the new report produced by UNDP, the United Nations Development Programme, released on 8 February 2022.

This dossier analyses the effects of armed conflicts and social protests on human security.

High development levels and widespread violence

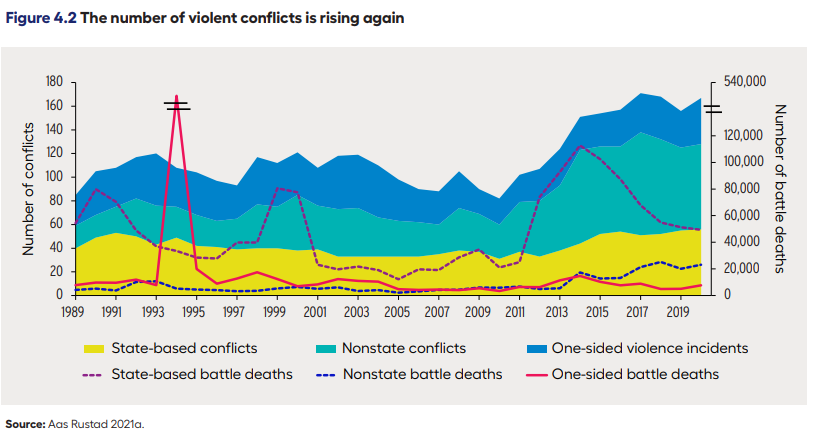

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, one hundred civilians were killed every day in armed conflicts and 1,205 people were victims of homicide around the world. The pandemic, according to the report, appears to have triggered an increase in intra-family violence and political violence. Today, conflict levels are high and although conflicts are apparently less deadly than in the past, violence is spreading in more countries. More people find themselves living in conflicts of various kinds and the majority of the world’s population feels insecure and threatened by violence.

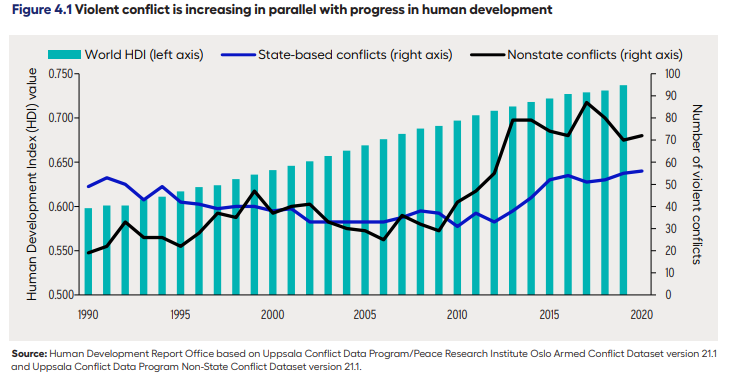

While up to now wars, violent conflicts between armed groups, violence, crime and unrest have been seen as a challenge to countries’ development, today the Pathways for Peace report by the UN and the World Bank has cast doubt on this assumption, claiming that ‘conflicts are increasing in parallel with human progress’. It also seems that violent conflicts are becoming more widespread in countries with a high human development index (the indicator that takes into account three elements: the level of health, the level of education, and the GDP per inhabitant).

One of the reasons driving this trend (which calls into question the mechanistic security-development relationship) is the fact that development has not benefited all people and has instead left many behind, paying maximum attention to economic growth and much less to equitable human development. A type of development, therefore, that has led to strong and growing inequalities, as well as increasing pressures on the planet.

All graphs below are derived from UNDP’s 2022 report. Cover image by Jonathan Harrison.

Social protests on the rise

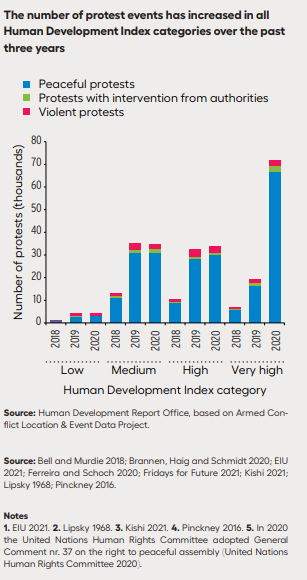

Over the last decade, social protests have multiplied worldwide, increasing in size and frequency. According to UNDP’s findings, the scale of recent protests is a symptom of insecurity and reveals deep rifts in societies and the failure of authorities to address citizens’ concerns.

Between 2009 and 2019, anti-government protests increased by an average of 11.5% per year, peaking in 2017 and 2019. In 2019, almost a quarter of residents in Hong Kong and Santiago de Chile (2million and 1.2million people respectively) took to the streets. The environmental movement Fridays for Future also recorded more than 4million attendances worldwide. These protests go hand in hand with a decline in trust in governments and democracy.

The number of protest events has increased overall over the past three years, with the largest increase occurring in countries with a high development index. The Covid-19 pandemic also contributed to this increase.

Who does what: the most impacted areas

South Asia reports the largest number of people affected by conflict, but in sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East about 30% of the population lives in widespread violence. Since the mid-2000s, the population affected by conflict in sub-Saharan Africa has increased significantly.

Arab countries have shown an increase in violence after 2011, since the post-Arab Spring period, particularly in Iraq, Syria and Yemen. Around 2016, there was also an increase in Latin America, mainly due to violence linked to the conflict between drug cartels in Brazil and Mexico. The Americas account for 40% of homicides: homicide rates have remained high and stable in the region, while they are declining in the rest of the world. In addition to homicides, people in Latin America are disproportionately exposed to other violent crimes.

FOCUS 1: long-term effects

Conflict has long-term negative effects on health systems, livelihoods and education. People living in conflict areas are exposed to aggravated health risks and are disproportionately affected by trauma and injury. These include mental health problems, which can lead to long-term disability and chronic illness. Conflict destroys health infrastructure and services, exacerbating people’s vulnerability to trauma and disease not directly related to combat. The conflict is also associated with increased sexual violence against women, higher rates of sexually transmitted diseases and deteriorating maternal health.

Food insecurity is higher in conflict-affected areas, which can cause malnutrition and lead to adverse health effects, particularly among children. Conflict and violence then trigger displacement, further exposing people to health threats. When large numbers of people are living in close proximity, outbreaks of life-threatening diseases such as cholera, malaria and Covid-19 are more likely to spread.

FOCUS 2: Everyday Peace Indicators

The Everyday Peace Indicators research group studies how villages and neighbourhoods perceive peace and related concepts such as coexistence, security and justice. Epi experiments with a bottom-up approach: instead of ‘experts’ or ‘scholars’ defining what peace means and looks like, communities define for themselves the everyday indicators they use to measure the success of peace in their own communities. Since these definitions may vary between communities, the indicators people use may also change.

Two examples are given in the UNDP report. The first, based on data collected from 1,500 people in 18 rural villages in eastern Afghanistan, reveals that roadblocks by rebel groups for the purpose of extortion were considered indicators of insecurity and conflict, while the proliferation of accessible public services or the visibility of women and girls in public spaces, such as the market, indicated a reduction in conflict.

Another example is Colombia. Here, the return of the local market and commerce in San Jose de Uruma in northeast Antioquia, hit hard by internal armed conflict, marked a transition to peace, while the accumulation of rubbish in the streets indicated a deterioration of the situation.