by Ambra Visentin

Wars and armies are accelerating the climate crisis. And as the major powers gather in Egypt for COP27 on climate, their political representatives are reluctant to talk about the elephant in the room: the decisive impact of the global military on the planet and its inhabitants, especially those in developing countries.

“The richest countries are spending 30 times as much on their armed forces as they spend on providing climate finance for the world’s most vulnerable countries, which they are legally bound to do”, reports the international research institute The Transnational Institute (TNI).

Data on the climate-damaging effects of war and armed forces are scarce, and information on emissions from military activities remains opaque and inaccessible. At the insistence of the United States, the armed forces were explicitly exempted from reporting domestic emissions when the Kyoto Protocol was negotiated in 1997. This exception was not renewed during the negotiations of the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, but even today each nation decides for itself whether the CO2 emissions of its armies must be collected and published. The reason: a CO2 footprint reveals information about troop size, vehicle fleets and manning of individual posts – and could therefore become a security policy risk for world military powers such as the US, Russia or China.

However, it is not difficult to imagine the magnitude of the climate impact of the increasingly advanced, more energy-intensive and more polluting armaments. The fuel tank of a Leopard 2 consumes an average of just over four litres of diesel and emits 1.5 kilograms of CO2 per kilometre, as reported by the Neue Zürcher Zeitung. The emissions of fighter jets are even higher: for each mission, a single jet emits around 28 tonnes of greenhouse gases into the air. And again, combat aircraft, such as the Rafale, consume more than 110 litres of fuel per minute.

Weapons are constantly being updated. And the newer they are, the more they pollute: F-35A fighters consume about 5,600 litres of oil per hour compared to 3,500 for the F-16 fighters that they are replacing. As military systems have a lifetime span of 30 to 40 years, this means locking-in highly polluting systems for many years to come.

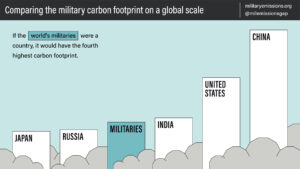

Another report, published by Conflict and Environment Watch (CEOBS) and Scientists for Global Responsibility, reveals that the military is responsible for at least 5.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions. The calculation includes not only war equipment, but also the operation of military facilities and the procurement of logistical and mission materials, from helmets to ready meals. The authors calculate that if all the world’s armies were a country, it would be the fourth largest emitter in the world, ahead of Russia. Looking instead at fuel consumption, TNI estimates that if the world’s armed forces were classified as one country, they would be the 29th largest oil consumer in the world, just ahead of Belgium and South Africa.

Seven of the top ten historical emitters are also among the top ten global military spenders: in order of magnitude the United States spends by far the most, followed by China, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, Japan and Germany. The other three of the top ten military spenders – Saudi Arabia, India and South Korea – are also high GHG emitters.

And now that the conflict in Ukraine is escalating daily, the arms race is gaining new momentum. A report by the Stockholm-based peace research institute Sipri shows that in 2021 global military spending has crossed the two trillion dollar threshold for the first time.

As the data show, Putin increased the defence budget by 3% before the invasion of Ukraine. However, the Russian government has already announced that it will increase the defence budget by another 20%. NATO for its part wants to increase its rapid reaction force from 40,000 to 300,000 soldiers. Japan plans to double its defence budget and China a seven per cent increase. Germany also wants to allocate a special fund of EUR 100 billion for national and alliance defence.

The military apparatus kills people and the planet. And it should be treated as a central issue at COP27. The Ukrainian government seems intent on treating it as such and is reportedly calculating the financial and environmental costs of the conflict’s impact on the climate – the first time a conflict-affected state has done so – to present the information at COP27.

Cover image: US Embassy Cairo on Flickr